The Evolving Role of the Board of Directors - Q&A with George Roberts

On our Boardspan Backchannel series, we talk to the world's most experienced and successful board members and corporate leaders to get their insights on the challenges that boards face today. In these conversations, you'll get an insider's view into navigating modern corporate governance.

In this Boardspan Backchannel conversation, George Roberts, Co-Founder and Co-CEO of KKR and a legendary investor deeply experienced board member and community advocate, joins Boardspan founder and CEO Abby Adlerman for a candid conversation about the evolving role of directors amid rising expectations and risks.

Abby Adlerman: George, thank you for spending some time with us. Let’s start with a big picture perspective: You started KKR in 1976, went on a few boards right away, and have been on many others since then. Can you tell us about the tone of boardrooms over the course of your career? How has being on a board evolved over time?

George Roberts: When we started, life was a lot simpler. On the private equity side, you made an investment in a company and the investors went on the board. Management was also an investor and owner of the business. Board meetings took two or three hours, focused on the business and what needed to be done.

On the public company side, boards have changed a lot in the 50 years I’ve been working. It used to be that there were no major governance people. CEOs picked their friends—that’s what the board was. I’m not sure outside directors had all that much knowledge or information about what was going on at that time unless there was a crisis. What started to happen in the late ‘60s, ‘70s and into the ‘80s is certain investors who are now called “activists” started doing hostile takeovers of companies. They would come in and make an offer for a company and that’s when the board would actually go into action. Out of that came all the rules about fiduciary duties, what boards are responsible for, independent committees— everything that we have today.

Then we had the Enron problems and the WorldCom problems and we wound up with Sarbanes-Oxley. It’s a totally different regime—what directors have to do, what you have to be aware of, what your obligations are. A lot of that is good. But most actions that I see boards having to take, both historically and now, is when some event takes place that disrupts the rhythm of that business.

AA: KKR is known for being a big player in private equity, but you’ve also sat on many public company boards. Presumably, a lot of the skills needed on a private board are similar to those of a public board. Do you see private and public companies having much in common when it comes to the role and skills of board members?

GR: I think they have a lot in common. As an example: In the ‘80s, Boone Pickens made a bid to buy Gulf Oil. We raised $12 billion in 1984 to make a competing bid —which we lost. Chevron ended up buying it. In our presentation to the board about how this was all going to work, we had a projection of $600 million in cost savings. I remember one of the directors turned to the CEO of Gulf, asking ‘Where did they get this number?’ And the CEO said, ‘I gave it to him. That’s what I think we could do.’ I’m sitting there thinking, if you’re a director of a company and there’s $600 million of savings that could be had, where have you been?

Again, a lot of this bubbles up because of a crisis or some event that comes about. In the private equity world we worry about those things all the time. We have processes in place and we bring people in to help—and the whole management team is engaged because that is mainly how they get paid, through the equity value that is created. I think it’s really hard in a large public company to have the same alignment of interest and the same kind of laser focus on creating long-term value. And that’s where I think the paths diverge quite a bit.

AA: Yes, long-term perspective can be a challenge and whether being in the public markets detracts from that focus is certainly something boards think about. What else gets in the way?

GR: There’s always going to be stuff coming at you that you don’t expect as a director. The more knowledgeable you are about the company itself and the people there, the better your ability to handle that.

We over-educate everybody on the KKR board. We have members who are very financially sophisticated and that makes me feel very good because they really understand the numbers. And we have people with very deep experience in various fields. We have an eclectic group for good reason. In addition, we hold a board dinner where we invite 10 or 12 others from our team, often at the partner-level. Directors can ask any questions they want and over the course of five meetings they get to know 50 people within our organization.

Most board meetings today last a day and a half—a lot of that is procedure, what the law requires. But if that’s all you do, then you are not spending enough time with the people in the company—you’re really not worrying about what the company’s culture and values are. Walk around the office and get to know people. Pull some younger person out and go spend some time with them. You will learn a lot more that way.

I think the number one responsibility of any director is to make sure you have the right management, the right CEO, both in terms of the person in the seat and potential successors.

Also, compensation and promotion motivates people. You will get the results out of what you set up—it happens every time. So, pay attention to the dollars that are paid not just to the top management, but to others. That will give you a pretty good sense of what’s going on.

AA: Now let’s hone in on the events that disrupt a business. What are your thoughts about managing a crisis?

GR: The mistake people make when there’s a crisis is not getting it all out there right away and admitting that, ‘hey, this is a mistake, this is what happened and here’s what we’re going to try and do about it.’ Instead of one or two headlines, you’ll have weeks of them if you don’t really go out to the communities being affected and talk honestly about what’s going on. At KKR we tell everybody, the good news can wait, tell us about the bad news. Shine a light on it: That’s the best way to contain and even make something good come out of a problem.

AA: So, George, are you an advocate of boards doing “what if” crisis planning or scenario planning?

GR: Sure. A lot of people on our board and in our firm spend time on cyber security, for example. Every CEO, every board, should be worried about that. We have seen not only the damage, but the embarrassment that comes with hacks. That’s not going away. The bad guys are going to keep getting smarter and staying ahead of you. I’ll guarantee you that there is no system around, including NSA, that can’t be hacked if somebody makes up their mind to do that.

You’ve also got to put processes in place and work with your people and train them to do what’s right in terms of harassment and everything else. Directors need to know that the company has the processes and attention to handle those kinds of issues that come up.

We try to give our directors a job beyond sitting in the boardroom and listening to presentations and asking smart questions. So we have a group that’s working on diversity. We have a group that’s working on where we should be 20 years from now. The best way to get the most out of the directors is to get them involved. When they’re in town, they’re invited to go talk to anyone they want to talk to, which is good—they get a pretty good sense of what is going on.

AA: Impressive stuff. So now I’ll take the gloves off: Do you have an example of a crisis you were involved in and what you learned from it?

GR: Well, we bought Toys ‘R Us a number of years ago – before Amazon, and before Walmart started treating toys as a loss leader, driving all the profit out of the industry. We brought in new management, put more money in, and the company was growing for the first several years – new stores, international footprint but in the past few years, it became obvious that the company couldn’t compete with the Amazon effect. We put forth a plan to restructure it in Chapter 11, to reduce the debt, wipe out our investment and still have Toys ‘R Us continue on as a successful organization.

The crisis happened when some hedge funds bought some of the debt very cheaply, which became the fulcrum security. Instead of reorganization, they pushed for liquidation. In the 50 years I have been doing this, I’ve been involved in over 450 transactions and while not all of them worked, this was the first forced liquidation of a business like this. We didn’t think that was going to happen and we weren’t prepared, quite frankly, for the fallout, which was the loss of all the U.S. jobs. It’s a sad situation that didn’t have to happen, and I ask myself what could we have done differently to avoid it.

I am not proud of the situation, but I am proud of what we did: We took leadership and we said, legally we are not required to do anything, but it’s the right thing for us to do something to help the workers. It was complicated because if we put money into Toys ‘R Us, which was in liquidation, it would go to the creditors. But we wanted money to go to the 22,000 laid off people who really needed it. We set up a separate entity and got a really good person to administer it. We put $10 million in and asked our two partners to do the same. One said no, but one put in $10 million. We went to the creditors who forced the liquidation and so far they have said no. We then went to some others who were willing to contribute. So we created a pool of capital and had to make sure we got the funds to the people who need it.

Both in our decision to fund this and also in deciding how the funds would be distributed, we partnered with former TRU employee leaders and some worker advocates, including folks who had been critical of our approach. We decided to sit down and talk to them. We might disagree on some things but let’s at least have a conversation on where we could agree. And together we created an unprecedented approach (in the US) to help workers in a liquidation. One thing I’ve learned over the years: Any time you have a conflict with someone, go sit down and talk to them. Don’t have your lawyer start writing letters.

AA: Wow, that sounds like a Herculean effort. Thanks for sharing the inside perspective with us. To close out, everyone who sits on a board these days is dealing with myriad issues. As a public board member today, what advice do you have for others?

GR: As a director, I would really want to educate myself on what the business does. I would want to make sure that, without interfering in the business operations, I had access to everything I wanted to have access to. I would want to walk into the business and just talk to people. I would want to know that the company has ‘break the glass’ measures in place and what they are. If a crisis takes place, do they have good crisis management people with communications abilities? It all sounds simple, but it’s not always easy to know exactly what drives things.

AA: George Roberts, it has been an absolute pleasure to spend time with you. Thank you for your generosity of spirit and sharing such valuable insights with all of us in the board and governance community.

How can your board evolve and succeed this year?

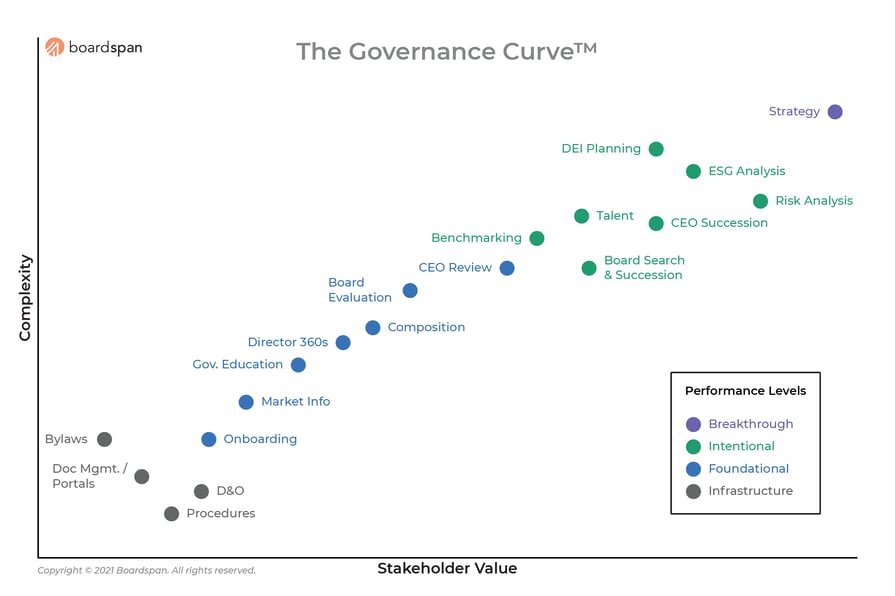

How do you go from simply checking the boxes to adding significant strategic value to your organization? It's all about moving up the Governance Curve.

To learn more about the Governance Curve and how to move up and to the right, download our ebook, The Governance Curve: A New Way to Think About Board Success.

[photo by Linus Nyland at Unsplash]